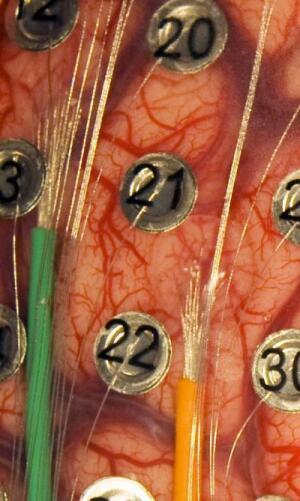

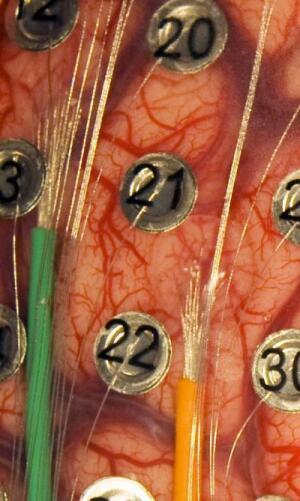

Microelectrodes on the brain

Photo: University of Utah

Department of Neurosurgery

Experimental devices that read brain signals have helped paralyzed people use computers and may let amputees control bionic limbs. But existing devices use tiny electrodes that poke into the brain. Now, a University of Utah study shows that brain signals controlling arm movements can be detected accurately using a new type of micro electrode that sits on the brain but doesn't penetrate it.

"The unique thing about this technology is that it provides lots of information out of the brain without having to put the electrodes into the brain," says Bradley Greger, an assistant professor of bioengineering and coauthor of the study. "That lets neurosurgeons put this device under the skull but over brain areas where it would be risky to place penetrating electrodes: areas that control speech, memory and other cognitive functions."

For example, the new array of microelectrodes someday might be placed over the brain's speech center in patients who cannot communicate because they are paralyzed by spinal injury, stroke, Lou Gehrig's disease or other disorders, he adds. The electrodes would send speech signals to a computer that would convert the thoughts to audible words.

For people who have lost a limb or are paralyzed, "this device should allow a high level of control over a prosthetic limb or computer interface," Greger says. "It will enable amputees or people with severe paralysis to interact with their environment using a prosthetic arm or a computer interface that decodes signals from the brain."

The study is in the July 1 online journal Neurosurgical Focus.

Converting Thoughts to Movement

The findings represent "a modest step" toward use of the new microelectrodes in systems that convert the thoughts of amputees and paralyzed people into signals that control lifelike prosthetic limbs, computers or other devices to assist people with disabilities, says University of Utah neurosurgeon Paul A. House, the study's lead author.

"The most optimistic case would be a few years before you would have a dedicated system," he says, noting more work is needed to refine computer software that interprets brain signals so they can be converted into actions, like moving an arm.

Such technology already has been developed in experimental form using small arrays of penetrating electrodes that stick into the brain. The University of Utah pioneered development of the 100-electrode Utah Electrode Array used to read signals from the brain cells of paralyzed people. In experiments in Massachusetts, researchers used the small, brain-penetrating electrode array to help paralyzed people move a computer cursor, operate a robotic arm and communicate.