Taking the mystery out of breast density

July 02, 2018

by John R. Fischer, Senior Reporter

Ten years ago, any level of information about breast density was not required to be shared with women after their mammogram.

Now such a fact or general summaries on the topic are required in more than 30 states with Wisconsin being the most recent to pass a bill on the matter, spearheaded by U.S. Representative Mike Rohrkaste."

For Rohrkaste, inspiration came from constituent, Gail Zeamer, a Neenah resident diagnosed in 2016 with stage 3C breast cancer that had spread to her lymph nodes. Zeamer, who had received three normal mammograms over the last two years, found out she had cancer through an ultrasound scan. When asked why it was not detected on her mammograms, doctors told her it was because she had dense breast tissue which masked the tumors from being seen during the exams.

When she asked why she had not been informed of this, doctors simply said they did not tell patients that information. Shocked and angered, Zeamer contacted Rohrkaste and other constituents to form a law that would require doctors to inform women of this matter so that others would not go through her ordeal.

“This is a good first step because women are now alerted to this in the report that goes to them,” Rohrkaste, told HealthCare Business News, adding that his own wife, also named Gail, knows she has dense breasts because of his involvement in the matter. “This will help educate doctor’s offices and lead to questions by providers and patients.”

Zeamer’s story is one shared by women worldwide who only learned what breast density was when informed that it was the reason why their mammograms did not detect their cancer earlier.

But legislative efforts, research, and technological advancements are putting breast density at the forefront of a national conversation, according to experts who hope that such discussions will lead to greater awareness among professionals outside of radiology and enable earlier access to treatment.

Lack of awareness

About 40-50 percent of women throughout the U.S. have dense breasts. A 2017 study of 200,000 patients published in the JAMA Journal of American Association Oncology found breast density outweighed all other risk factors for breast cancer, including family history.

“I think that’s significant because practitioners and patients have been under the impression that if they have a family history, there’s a risk there. If they don’t, it’s not a problem,” said Dr. Monica Saini, a consultant diagnostic radiologist for Volpara Health Solutions. “This is incorrect because radiologists know that when we diagnose breast cancer, about 70 percent of those are cases where women have no family history.”

The topic of breast density, according to Saini, has only become widely discussed among research circles in the last ten years, with some radiologists at odds on the best course of action to take. While some favor supplemental testing, others say what they look for in mammograms has to change.

With no consensus on a next step, many are hesitant to share their views on breast density with referring physicians and other non-radiologists for fear of spreading misinformation and causing patients potentially unnecessary anxiety.

Dr. Emily Conant, chief of the division of breast imaging in the University of Pennsylvania’s department of radiology and a consultant for iCAD Inc. and Hologic, is an advocate of informing women about their breast density and discussing the pros and cons of supplemental screening. She is concerned, however, that not all patients have access to supplemental screening due to additional costs.

“Women in some states have to pay out-of-pocket for supplemental screening. It’s distressing that supplemental screening may be more accessible to those that can afford it and not to those who can’t,” she said. “The potential additional cost, however, is not a good reason for physicians to not inform women about their breast density.”

In agreement with Conant is U.S. Senator Christine Rolfes who, like Rohrkaste, recently celebrated the passage of her own bill for breast density legislation in her home state of Washington. “When I first found out about breast density in 2012, the fight then was really about having insurance coverage for your basic mammogram, not anything more in-depth,” she said. “I think with the current state of breast density awareness and understanding, we’re starting at a very low level.”

Legislation

In 1994, Congress enacted the Mammography Quality Standards Act so that facilities nationwide would provide uniform quality standards to ensure early detection. Breast density, a little discussed topic at the time, was not included in these regulations.

That was supposed to change in 2011 when the MQSA committee of the FDA agreed to incorporate breast density assessment into MQSA standards. But seven years later, no changes have been made, a fact that boils the blood of Nancy Cappello, Ph.D., a survivor of stage 3C breast cancer whose own breast density experience propelled her to help pass the first state law in Connecticut in 2009 and found the nonprofits, Are You Dense Inc. and Are You Dense Advocacy Inc.

Cappello believes delays in incorporating these measures and the fact that no national law on breast density is in effect partially fall on the medical community for not showing greater support and speaking up about the issue.

“Radiologists, the Radiology Society and the Society of Breast Imaging haven’t come out in support of breast density legislations and haven’t even come out to tell doctors to just tell women and report it whether you have a state law or not,” she said. “Even if a woman knows she has dense breast tissue, it does not necessarily mean that she’s having informed conversations with her doctor.”

Senator Dianne Feinstein and Dean Heller introduced the Breast Density and Mammography Reporting Act of 2017 to the Senate floor in November to pave the way toward nationwide breast density legislation. A House counterpart is also being evaluated. In addition, new FDA commissioner Scott Gottlieb has promised to change breast density regulations as part of his 2018 plans. Both have instilled newfound optimism in Cappello.

“My hope is to change the MQSA, maybe through the FDA or with a national bill,” she said.

Emerging technological advantages

Two-dimensional mammography is considered the gold standard for breast cancer detection due to its low-dose X-ray nature and ability to produce high-quality images in shorter exam times. But with its reduced ability to detect lesions within dense breast tissue and the development of new and innovative technologies, experts are beginning to wonder if a better way for detecting cancer is on the way here.

Conant believes that tomosynthesis (or 3D mammography) is a significant improvement over 2D mammography due to fewer false positives and increased cancer detection. Synthetic 2D imaging with tomosynthesis allows the X-ray dose to be lower than imaging with a combination of 2D plus tomosynthesis.

She also believes the development of emerging technologies such as AI will help improve both the presentation of the image data and the detection of cancers. AI technologies have the potential to help the radiologist interpreting studies by improving both cancer detection and the efficiency of reading studies, even in dense, complex breast tissue patterns. Even tomosynthesis though will not find all cancers, since it is just an X-ray based exam without contrast.

“I think there will be a significant evolution of the imaging platform over time to account for those differences and to make it a better presentation that allows a quick overlook of the breast for density assessment and also lesion detection, where you look at the breast globally for asymmetries and changes over time,” she said.

The advent of AI is crucial to radiologists who foresee it as a point-of-reference for confirming their interpretation of findings, and as an assistant that can read images and reports at a greater pace, enabling quicker diagnoses and the onset of earlier treatments.

Rodney Hawkins, vice president of marketing for cancer detection at iCAD, believes this potential will further evolve with the integration of deep-learning and neural networks, enabling algorithms to learn for themselves rather than being taught by radiologists.

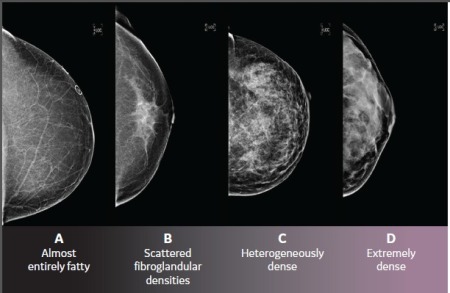

“We can train algorithms on thousands of cancer cases or breast density cases. You can show it breast images of different densities and those images get annotated by a radiologist,” he said. “You can tell it this is category A, B, C, or D, and then that algorithm learns from the annotated images what falls into what category. It’s able to learn much faster by showing it the images.”

AI is expected to transform imaging modalities like automated ultrasound systems and breast MR. Luke Delaney, general manager of automated breast ultrasound at GE Healthcare, said that in addition to improving breast density assessment, machine learning and other advancements could enable automated devices such as GE’s ABUS to tailor care on an individual level.

“One of the things we’re working on with customers and patients is the right combinations of technologies that work together to find as many cancers as possible and keep recall rates and false positives low,” he said. “How they should be used together for each patient and her own profile is one of the big areas of research as well.”

Experts agree that in order to capitalize on these potential capabilities, greater access to data is needed. Providers can help in this endeavor by retaining and utilizing all information at their disposal, including raw data of mammographic images, which often are disposed of and not stored in PACS so hospitals and clinics won’t have to double storage capacity.

“Not having access to historical mammograms limits the capacity to compare breast density between current and prior mammograms,” said Mohamed Abdolell, CEO of Densitas Inc. “Integration directly with FFDM scanners is required when processing raw images, adding integration burden and costs, and typically requiring more effort, time and complexity of ongoing support.”

A quantitative future

Masking tumors on mammograms is only one of the risks that dense tissue poses. The very presence of dense breast tissue indicates that a woman is at greater risk of developing breast cancer.

Dr. Conant believes that the most accurate and reproducible way to measure breast density is using quantitative measures rather than more subjective or potentially variable qualitative assessments. “There’s a big move to have breast density or “complexity” measured quantitatively with robust and reproducible computer algorithms. These quantitative measures can help us better understand why some cancers aren’t detected with mammography alone, while also providing insight into cancer subtypes and breast cancer risk. We believe this image data will better inform radiologists and healthcare providers which screening test or tests are best for an individual woman.”

Dr. Saini echoes this sentiment, adding that the density-cancer link and limitations in mammography must be taught to a greater extent in medical schools, and that models such as BI-RADS can only truly reflect the best approach for detecting cancer once standardization is in place.

“Having every state do a different thing creates more confusion,” she said. “We have to have a national, uniform conversation, which means it’s going to be probably at the level of the FDA to mandate a uniform approach to this. If we have an automated standardized way of assessing density across our population and the world, then we can track who are the women at greater risk.”

She does, however, note that research for new technologies in this area are on the rise and will help to relieve not just the challenges of breast density assessment and cancer detection but other burdens, such as the increasing shortage of radiologists worldwide.

Experts agree that awareness is growing, as evidenced by the more than 30 states with mammography laws, and that further growth must be facilitated by all parties, from legislatures and medical practitioners to manufacturers and patients.

“Manufacturers must demonstrate more that their products are cost-effective and improve clinical outcomes,” Abdolell said. “They can do this by providing the opportunities to validate their technologies to support researchers and breast imaging centers. Patients, too, need to take more ownership of being aware of their health because of the structure of payers and insurers. They have to be self-advocates. That’s how it moves into the realm of legislation.”

Now such a fact or general summaries on the topic are required in more than 30 states with Wisconsin being the most recent to pass a bill on the matter, spearheaded by U.S. Representative Mike Rohrkaste."

For Rohrkaste, inspiration came from constituent, Gail Zeamer, a Neenah resident diagnosed in 2016 with stage 3C breast cancer that had spread to her lymph nodes. Zeamer, who had received three normal mammograms over the last two years, found out she had cancer through an ultrasound scan. When asked why it was not detected on her mammograms, doctors told her it was because she had dense breast tissue which masked the tumors from being seen during the exams.

When she asked why she had not been informed of this, doctors simply said they did not tell patients that information. Shocked and angered, Zeamer contacted Rohrkaste and other constituents to form a law that would require doctors to inform women of this matter so that others would not go through her ordeal.

“This is a good first step because women are now alerted to this in the report that goes to them,” Rohrkaste, told HealthCare Business News, adding that his own wife, also named Gail, knows she has dense breasts because of his involvement in the matter. “This will help educate doctor’s offices and lead to questions by providers and patients.”

Zeamer’s story is one shared by women worldwide who only learned what breast density was when informed that it was the reason why their mammograms did not detect their cancer earlier.

But legislative efforts, research, and technological advancements are putting breast density at the forefront of a national conversation, according to experts who hope that such discussions will lead to greater awareness among professionals outside of radiology and enable earlier access to treatment.

Lack of awareness

About 40-50 percent of women throughout the U.S. have dense breasts. A 2017 study of 200,000 patients published in the JAMA Journal of American Association Oncology found breast density outweighed all other risk factors for breast cancer, including family history.

“I think that’s significant because practitioners and patients have been under the impression that if they have a family history, there’s a risk there. If they don’t, it’s not a problem,” said Dr. Monica Saini, a consultant diagnostic radiologist for Volpara Health Solutions. “This is incorrect because radiologists know that when we diagnose breast cancer, about 70 percent of those are cases where women have no family history.”

The topic of breast density, according to Saini, has only become widely discussed among research circles in the last ten years, with some radiologists at odds on the best course of action to take. While some favor supplemental testing, others say what they look for in mammograms has to change.

With no consensus on a next step, many are hesitant to share their views on breast density with referring physicians and other non-radiologists for fear of spreading misinformation and causing patients potentially unnecessary anxiety.

Dr. Emily Conant, chief of the division of breast imaging in the University of Pennsylvania’s department of radiology and a consultant for iCAD Inc. and Hologic, is an advocate of informing women about their breast density and discussing the pros and cons of supplemental screening. She is concerned, however, that not all patients have access to supplemental screening due to additional costs.

“Women in some states have to pay out-of-pocket for supplemental screening. It’s distressing that supplemental screening may be more accessible to those that can afford it and not to those who can’t,” she said. “The potential additional cost, however, is not a good reason for physicians to not inform women about their breast density.”

In agreement with Conant is U.S. Senator Christine Rolfes who, like Rohrkaste, recently celebrated the passage of her own bill for breast density legislation in her home state of Washington. “When I first found out about breast density in 2012, the fight then was really about having insurance coverage for your basic mammogram, not anything more in-depth,” she said. “I think with the current state of breast density awareness and understanding, we’re starting at a very low level.”

Legislation

In 1994, Congress enacted the Mammography Quality Standards Act so that facilities nationwide would provide uniform quality standards to ensure early detection. Breast density, a little discussed topic at the time, was not included in these regulations.

That was supposed to change in 2011 when the MQSA committee of the FDA agreed to incorporate breast density assessment into MQSA standards. But seven years later, no changes have been made, a fact that boils the blood of Nancy Cappello, Ph.D., a survivor of stage 3C breast cancer whose own breast density experience propelled her to help pass the first state law in Connecticut in 2009 and found the nonprofits, Are You Dense Inc. and Are You Dense Advocacy Inc.

Cappello believes delays in incorporating these measures and the fact that no national law on breast density is in effect partially fall on the medical community for not showing greater support and speaking up about the issue.

“Radiologists, the Radiology Society and the Society of Breast Imaging haven’t come out in support of breast density legislations and haven’t even come out to tell doctors to just tell women and report it whether you have a state law or not,” she said. “Even if a woman knows she has dense breast tissue, it does not necessarily mean that she’s having informed conversations with her doctor.”

Senator Dianne Feinstein and Dean Heller introduced the Breast Density and Mammography Reporting Act of 2017 to the Senate floor in November to pave the way toward nationwide breast density legislation. A House counterpart is also being evaluated. In addition, new FDA commissioner Scott Gottlieb has promised to change breast density regulations as part of his 2018 plans. Both have instilled newfound optimism in Cappello.

“My hope is to change the MQSA, maybe through the FDA or with a national bill,” she said.

Emerging technological advantages

Two-dimensional mammography is considered the gold standard for breast cancer detection due to its low-dose X-ray nature and ability to produce high-quality images in shorter exam times. But with its reduced ability to detect lesions within dense breast tissue and the development of new and innovative technologies, experts are beginning to wonder if a better way for detecting cancer is on the way here.

Conant believes that tomosynthesis (or 3D mammography) is a significant improvement over 2D mammography due to fewer false positives and increased cancer detection. Synthetic 2D imaging with tomosynthesis allows the X-ray dose to be lower than imaging with a combination of 2D plus tomosynthesis.

She also believes the development of emerging technologies such as AI will help improve both the presentation of the image data and the detection of cancers. AI technologies have the potential to help the radiologist interpreting studies by improving both cancer detection and the efficiency of reading studies, even in dense, complex breast tissue patterns. Even tomosynthesis though will not find all cancers, since it is just an X-ray based exam without contrast.

“I think there will be a significant evolution of the imaging platform over time to account for those differences and to make it a better presentation that allows a quick overlook of the breast for density assessment and also lesion detection, where you look at the breast globally for asymmetries and changes over time,” she said.

The advent of AI is crucial to radiologists who foresee it as a point-of-reference for confirming their interpretation of findings, and as an assistant that can read images and reports at a greater pace, enabling quicker diagnoses and the onset of earlier treatments.

Rodney Hawkins, vice president of marketing for cancer detection at iCAD, believes this potential will further evolve with the integration of deep-learning and neural networks, enabling algorithms to learn for themselves rather than being taught by radiologists.

“We can train algorithms on thousands of cancer cases or breast density cases. You can show it breast images of different densities and those images get annotated by a radiologist,” he said. “You can tell it this is category A, B, C, or D, and then that algorithm learns from the annotated images what falls into what category. It’s able to learn much faster by showing it the images.”

AI is expected to transform imaging modalities like automated ultrasound systems and breast MR. Luke Delaney, general manager of automated breast ultrasound at GE Healthcare, said that in addition to improving breast density assessment, machine learning and other advancements could enable automated devices such as GE’s ABUS to tailor care on an individual level.

“One of the things we’re working on with customers and patients is the right combinations of technologies that work together to find as many cancers as possible and keep recall rates and false positives low,” he said. “How they should be used together for each patient and her own profile is one of the big areas of research as well.”

Experts agree that in order to capitalize on these potential capabilities, greater access to data is needed. Providers can help in this endeavor by retaining and utilizing all information at their disposal, including raw data of mammographic images, which often are disposed of and not stored in PACS so hospitals and clinics won’t have to double storage capacity.

“Not having access to historical mammograms limits the capacity to compare breast density between current and prior mammograms,” said Mohamed Abdolell, CEO of Densitas Inc. “Integration directly with FFDM scanners is required when processing raw images, adding integration burden and costs, and typically requiring more effort, time and complexity of ongoing support.”

A quantitative future

Masking tumors on mammograms is only one of the risks that dense tissue poses. The very presence of dense breast tissue indicates that a woman is at greater risk of developing breast cancer.

Dr. Conant believes that the most accurate and reproducible way to measure breast density is using quantitative measures rather than more subjective or potentially variable qualitative assessments. “There’s a big move to have breast density or “complexity” measured quantitatively with robust and reproducible computer algorithms. These quantitative measures can help us better understand why some cancers aren’t detected with mammography alone, while also providing insight into cancer subtypes and breast cancer risk. We believe this image data will better inform radiologists and healthcare providers which screening test or tests are best for an individual woman.”

Dr. Saini echoes this sentiment, adding that the density-cancer link and limitations in mammography must be taught to a greater extent in medical schools, and that models such as BI-RADS can only truly reflect the best approach for detecting cancer once standardization is in place.

“Having every state do a different thing creates more confusion,” she said. “We have to have a national, uniform conversation, which means it’s going to be probably at the level of the FDA to mandate a uniform approach to this. If we have an automated standardized way of assessing density across our population and the world, then we can track who are the women at greater risk.”

She does, however, note that research for new technologies in this area are on the rise and will help to relieve not just the challenges of breast density assessment and cancer detection but other burdens, such as the increasing shortage of radiologists worldwide.

Experts agree that awareness is growing, as evidenced by the more than 30 states with mammography laws, and that further growth must be facilitated by all parties, from legislatures and medical practitioners to manufacturers and patients.

“Manufacturers must demonstrate more that their products are cost-effective and improve clinical outcomes,” Abdolell said. “They can do this by providing the opportunities to validate their technologies to support researchers and breast imaging centers. Patients, too, need to take more ownership of being aware of their health because of the structure of payers and insurers. They have to be self-advocates. That’s how it moves into the realm of legislation.”