Get ready: UDI rule could affect providers, too

July 05, 2012

by Brendon Nafziger, DOTmed News Associate Editor

After half a decade of conferences, workshops, pilot studies, the lobbying for legislation and the passage of legislation, and even angry letters from long-serving U.S. senators against a seemingly obstructionist executive office, the unique device identifier (UDI) rule has, at last, arrived.

The Food and Drug Administration released proposed rules for tracking medical devices Tuesday, ahead of the December 31 deadline it would have been given by a clause in a new FDA user fee renewal bill, which Congress passed last month and President Obama is expected to soon sign.

Proponents of the new device identification system say it could have far-reaching effects on U.S health care by allowing easier tracking of recalled products, as well as helping hospitals better manage their inventories and keep expired items off their shelves. They also say it could improve clinical care by, for instance, letting paramedics know the kind of implant someone has before they even reach the hospital.

But while the expense, and hassle, of implementing UDIs will now primarily affect suppliers, who will have to tweak their production processes, if they haven't already, many of the program's predicted benefits can only be realized once providers start incorporating UDIs into their workflow. And it's possible, too, that the government will not wait for providers to do this on their own.

"In an early version of the Affordable Care Act, there was language that would have required capturing UDI in electronic medical records," said Karen Conway, executive director of GHX, a supply chain automation company that has been working with the FDA to test aspects of UDI implementation. Although she said it was later struck from the law, Conway maintains that the Office of the National Coordinator and the FDA are still having conversations about the matter.

"If I were a betting person, I would say it could happen down the road," she said.

HOW THE UDI WORKS

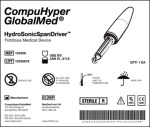

The UDI is essentially a number that identifies a particular medical device. As Conway explains, it would be graphically represented on an item in the form of a barcode, RFID or other machine-readable identifier. The identifier in turn will point to a database that lists different attributes of the product that could have regulatory or even clinical significance, such as its size and whether it's sterile or contains latex.

The database is, in many ways, the key to the whole endeavor, but it still has to be forged. GHX, along with its partners, worked on a pilot test of a prototype database for the FDA in 2009. The problem is the distributed nature of medical device data. The attributes needed for the database are often kept on different systems -- some clinical, some supply chain -- and they have to all be pooled into one place. GHX is also currently working with the Global Data Synchronization Network, an FDA partner organization, on external User Acceptance Testing for the agency -- that is, to see if the database works as intended and meets its users needs. Later, the FDA would likely work with the Association for Healthcare Resource & Materials Management (AHRMM), the supply chain wing of the American Hospital Association, to test how hospitals and others access data from the database, Conway said.

ORIGINS WITH THE IOM

Although the latest version of the proposed rules only came out this week -- and as of this writing have not even been printed up by the Federal Register yet -- the UDI has actually been a long time coming.

According to Conway, its origins lie, ultimately, in the Institute of Medicine's influential 1999 report on medical errors, "To Err Is Human," which in turn was the catalyst for a 2006 national drug bar code rule, which improved the tracking of pharmaceutical shipments. As Conway explained, the FDA's device office realized it wanted something similar for devices, and in 2007, Congress passed a law that required the agency to implement UDIs.

But here's where things get tricky. The FDA's original proposed UDI rule was actually released in July 2011, but was then held by the Office of Management and Budget, in charge of reviewing these things, ever since. Under a standing executive order, the OMB has only 90 days to make a decision, or request another 30-day extension, on the rules it's examining. But for reasons no one outside the OMB really knows, the office exceeded its allotted time. In fact, this past February, Sens. Herb Kohl (D-Wis.), Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa) and Richard Blumenthal (D.-Conn.) wrote a letter to the OMB, urging it to hurry up.

Although it's not really known what caused the snag, on her GHX blog, Conway suggested that maybe the Obama administration was reluctant to stack one more regulation on the medical community on the heels of meaningful use, ICD-10 and the health reform changes.

"I would guess there's probably some politics involved in health care," she joked, when DOTmed News spoke with her by phone.

BETTER TRACKING, COMING SOON

For now, though, the UDI is back on track. According to language in the FDA user fee bill, within two years of final regulations being issued, implantable devices would have to bear UDIs. As the FDA released its new proposed rules this week, with an accompanying 120-day comment period, this means the UDI should be working by 2015 -- at least for riskier, implantable medical devices, like pacemakers and orthopedic implants, following the FDA's risk-based approach.

But once the system's up and running, what kinds of benefits will the U.S. health care system see?

The oft-mentioned primary goal of the program is making it easier to track down recalled devices. "I suspect (hospitals) do a pretty good job (with this), but it comes at the expense of extra labor," Conway said. She said without the ability to capture data in a standardized format in a central system, recall notices can be a hassle. Hospital or clinic staff have to ask: did they buy the product? If they did, did they use it? And if so, where is it now?

But there are other, really non-clinical applications that could also help by taking some of the waste out of the supply chain, according to Conway.

For instance, UDIs could lead to better stocking practices, by letting materials managers or other supply chain personnel get a better grasp of how much extra and even soon-to-expire inventory they have on their shelves. Conway said that while hard data were lacking she had heard from at least one supplier that they had two years' worth of inventory in the field due to expire in the next 18 months.

"In health care, traditionally, we tend to focus more on what we buy and how much, and at what price, and not as much on what products we're using or how much we're actually consuming," she said.

Then there's billing, which Conway said is rife with errors related to device capture. One of her colleagues, for instance, studied the clinical supply documentation at a large teaching hospital's endovascular operating room. Of the 100 cases examined over a three-month period, all had data capturing errors for charges, with most both over-billing and under-billing at the same time: 90 percent under-billed and 80 percent over-billed, she said.

"Supply documentation is done with paper logs, with stickers on paper, or even when there's an automated system you have to manually enter the data," she said. "And whenever you manually enter things, if you type like I do, there are problems."

COMING DOWN THE LINE

To reap the benefits, though, health care providers will have to have processes in place to take full advantage of UDIs. With that in mind, Conway has offered these four tips for hospitals and clinics hoping to implement the program once it's working:

Identify stakeholders: Find out who should be involved in your UDI implementation committees, and who should be aware of what's going on. And it's not just supply chain personnel. Also involved are circulating nurses who currently capture lot and serial numbers on products, IT folks who set up EMRs and handle meaningful use compliance and even doctors and surgeons who, at the end of the day, need to be on board with the changes.

Educate: Supply chain personnel might be following the UDI developments, but not everyone else is. Conway said once you've ID'd your stakeholders, it's important to educate them on all the associated legislation and regulations. Plus, it's critical that they be aware of not just the what, but the why. "If they don't see the value that it has, then it will look like another regulation, as opposed to something that will lower costs and improve efficacy," Conway said.

Learn how to share: Hospitals or clinics will need to get usable information from the UDI and figure out how to share it across systems: from supply chain software to financial programs, from implant logs recorded by circulating nurses to clinical systems. "How do I internally, within my four walls, share this information? And ideally, how do I share information with my suppliers?" Conway asked.

Scan it: According to the new rules, FDA requires UDIs to be both human ("plain text") and machine-readable. But if you want them read by machines, you'll need to purchase the machines that can do it. "Do you need to be invested in some kind of point-of-use capture technologies? It really depends," Conway said. Some hospitals are highly automated, and others are still very manual. For implants, for instance, the vast majority of sites still capture supply usage information during procedures on paper logs, she said. But digital capture, grabbing the info electronically at point of use and then possibly even incorporating it into the EMR, could let providers get the most out of the process. That's something, by the way, that has never really happened with the medication bar code system. Even though it took effect in 2006, today only 40 percent of hospitals are fully using bar codes, Conway said. "They are not achieving its full potential."

The Food and Drug Administration released proposed rules for tracking medical devices Tuesday, ahead of the December 31 deadline it would have been given by a clause in a new FDA user fee renewal bill, which Congress passed last month and President Obama is expected to soon sign.

Proponents of the new device identification system say it could have far-reaching effects on U.S health care by allowing easier tracking of recalled products, as well as helping hospitals better manage their inventories and keep expired items off their shelves. They also say it could improve clinical care by, for instance, letting paramedics know the kind of implant someone has before they even reach the hospital.

But while the expense, and hassle, of implementing UDIs will now primarily affect suppliers, who will have to tweak their production processes, if they haven't already, many of the program's predicted benefits can only be realized once providers start incorporating UDIs into their workflow. And it's possible, too, that the government will not wait for providers to do this on their own.

"In an early version of the Affordable Care Act, there was language that would have required capturing UDI in electronic medical records," said Karen Conway, executive director of GHX, a supply chain automation company that has been working with the FDA to test aspects of UDI implementation. Although she said it was later struck from the law, Conway maintains that the Office of the National Coordinator and the FDA are still having conversations about the matter.

"If I were a betting person, I would say it could happen down the road," she said.

HOW THE UDI WORKS

The UDI is essentially a number that identifies a particular medical device. As Conway explains, it would be graphically represented on an item in the form of a barcode, RFID or other machine-readable identifier. The identifier in turn will point to a database that lists different attributes of the product that could have regulatory or even clinical significance, such as its size and whether it's sterile or contains latex.

The database is, in many ways, the key to the whole endeavor, but it still has to be forged. GHX, along with its partners, worked on a pilot test of a prototype database for the FDA in 2009. The problem is the distributed nature of medical device data. The attributes needed for the database are often kept on different systems -- some clinical, some supply chain -- and they have to all be pooled into one place. GHX is also currently working with the Global Data Synchronization Network, an FDA partner organization, on external User Acceptance Testing for the agency -- that is, to see if the database works as intended and meets its users needs. Later, the FDA would likely work with the Association for Healthcare Resource & Materials Management (AHRMM), the supply chain wing of the American Hospital Association, to test how hospitals and others access data from the database, Conway said.

ORIGINS WITH THE IOM

Although the latest version of the proposed rules only came out this week -- and as of this writing have not even been printed up by the Federal Register yet -- the UDI has actually been a long time coming.

According to Conway, its origins lie, ultimately, in the Institute of Medicine's influential 1999 report on medical errors, "To Err Is Human," which in turn was the catalyst for a 2006 national drug bar code rule, which improved the tracking of pharmaceutical shipments. As Conway explained, the FDA's device office realized it wanted something similar for devices, and in 2007, Congress passed a law that required the agency to implement UDIs.

But here's where things get tricky. The FDA's original proposed UDI rule was actually released in July 2011, but was then held by the Office of Management and Budget, in charge of reviewing these things, ever since. Under a standing executive order, the OMB has only 90 days to make a decision, or request another 30-day extension, on the rules it's examining. But for reasons no one outside the OMB really knows, the office exceeded its allotted time. In fact, this past February, Sens. Herb Kohl (D-Wis.), Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa) and Richard Blumenthal (D.-Conn.) wrote a letter to the OMB, urging it to hurry up.

Although it's not really known what caused the snag, on her GHX blog, Conway suggested that maybe the Obama administration was reluctant to stack one more regulation on the medical community on the heels of meaningful use, ICD-10 and the health reform changes.

"I would guess there's probably some politics involved in health care," she joked, when DOTmed News spoke with her by phone.

BETTER TRACKING, COMING SOON

For now, though, the UDI is back on track. According to language in the FDA user fee bill, within two years of final regulations being issued, implantable devices would have to bear UDIs. As the FDA released its new proposed rules this week, with an accompanying 120-day comment period, this means the UDI should be working by 2015 -- at least for riskier, implantable medical devices, like pacemakers and orthopedic implants, following the FDA's risk-based approach.

But once the system's up and running, what kinds of benefits will the U.S. health care system see?

The oft-mentioned primary goal of the program is making it easier to track down recalled devices. "I suspect (hospitals) do a pretty good job (with this), but it comes at the expense of extra labor," Conway said. She said without the ability to capture data in a standardized format in a central system, recall notices can be a hassle. Hospital or clinic staff have to ask: did they buy the product? If they did, did they use it? And if so, where is it now?

But there are other, really non-clinical applications that could also help by taking some of the waste out of the supply chain, according to Conway.

For instance, UDIs could lead to better stocking practices, by letting materials managers or other supply chain personnel get a better grasp of how much extra and even soon-to-expire inventory they have on their shelves. Conway said that while hard data were lacking she had heard from at least one supplier that they had two years' worth of inventory in the field due to expire in the next 18 months.

"In health care, traditionally, we tend to focus more on what we buy and how much, and at what price, and not as much on what products we're using or how much we're actually consuming," she said.

Then there's billing, which Conway said is rife with errors related to device capture. One of her colleagues, for instance, studied the clinical supply documentation at a large teaching hospital's endovascular operating room. Of the 100 cases examined over a three-month period, all had data capturing errors for charges, with most both over-billing and under-billing at the same time: 90 percent under-billed and 80 percent over-billed, she said.

"Supply documentation is done with paper logs, with stickers on paper, or even when there's an automated system you have to manually enter the data," she said. "And whenever you manually enter things, if you type like I do, there are problems."

COMING DOWN THE LINE

To reap the benefits, though, health care providers will have to have processes in place to take full advantage of UDIs. With that in mind, Conway has offered these four tips for hospitals and clinics hoping to implement the program once it's working:

Identify stakeholders: Find out who should be involved in your UDI implementation committees, and who should be aware of what's going on. And it's not just supply chain personnel. Also involved are circulating nurses who currently capture lot and serial numbers on products, IT folks who set up EMRs and handle meaningful use compliance and even doctors and surgeons who, at the end of the day, need to be on board with the changes.

Educate: Supply chain personnel might be following the UDI developments, but not everyone else is. Conway said once you've ID'd your stakeholders, it's important to educate them on all the associated legislation and regulations. Plus, it's critical that they be aware of not just the what, but the why. "If they don't see the value that it has, then it will look like another regulation, as opposed to something that will lower costs and improve efficacy," Conway said.

Learn how to share: Hospitals or clinics will need to get usable information from the UDI and figure out how to share it across systems: from supply chain software to financial programs, from implant logs recorded by circulating nurses to clinical systems. "How do I internally, within my four walls, share this information? And ideally, how do I share information with my suppliers?" Conway asked.

Scan it: According to the new rules, FDA requires UDIs to be both human ("plain text") and machine-readable. But if you want them read by machines, you'll need to purchase the machines that can do it. "Do you need to be invested in some kind of point-of-use capture technologies? It really depends," Conway said. Some hospitals are highly automated, and others are still very manual. For implants, for instance, the vast majority of sites still capture supply usage information during procedures on paper logs, she said. But digital capture, grabbing the info electronically at point of use and then possibly even incorporating it into the EMR, could let providers get the most out of the process. That's something, by the way, that has never really happened with the medication bar code system. Even though it took effect in 2006, today only 40 percent of hospitals are fully using bar codes, Conway said. "They are not achieving its full potential."